Celebrating Black Queer Icons for Black History Month

Queer inclusion must always be intersectional.

These Black LGBTQIA+ icons were important trailblazers in their time, breaking the barriers of race, gender, and sexuality. Their legacies continue to inspire us all to live authentic lives and commit ourselves to creating a world where everyone can thrive.

While uncovering queer histories previous to the 1900s is difficult for any historian, uncovering Black Queer histories is even more difficult because how archives were created and continue to be researched. It is amazing to consider that these eight icons span generations from the Emancipation Proclamation to today, and humbling to consider the stories yet to be discovered.

Marsha P. Johnson (1945 - 1992)

Marsha P. Johnson was an integral part of the LGBTQ+ rights movement in New York City in the 1960s and 70s. Assigned male at birth, Marsha was bullied and assaulted as a child. Scarce protections for and inclusion of LGBTQ+ people resulted her turning to sex work to survive. She was present at 1969 Stonewall riots, which motivated her activism.

Black and trans people were not welcome in many gay activist spaces, so she and Sylvia Riveria started “Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries” for youth, continuing to be vocal about Black, trans, and HIV+ issues.

She was found dead in the Hudson River under suspicious circumstances in 1992.

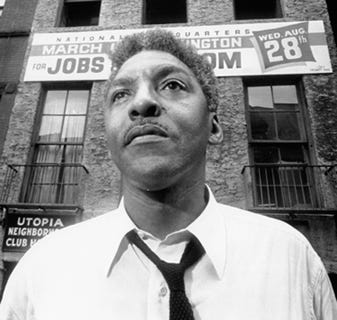

Bayard Rustin (1912 - 1987)

Bayard Rustin is best known as a trusted advisor of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Grounded in a Quaker upbringing, his activism began in 1940s, when he coordinated nonviolent protests and lectures combating segregation.

However, his socialist views and homosexuality were not accepted during the height of the Red and Lavender Scares, so he kept to the background of the civil rights movement. Therefore, he lesser known than other civil right activists for his essential contributions to the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Congress of Racial Equality, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

Gladys Bentley (1907 - 1960)

The Harlem Renaissance was a center of Black and Queer culture during the 1930s.

Gladys Bentley - who sometimes used the stage name Bobbie Minton - was know for her gender-bending style, especially her iconic white tailcoat and top hat. She was out as a lesbian, often referring to female lovers in her performances or re-writing popular songs to be about loving women.

In the 1940s and 50s, the Red Scare targeted speculated communists, as well as queer people, so Gladys made the difficult decision to live in the closet, adopt traditionally feminine dress, and claimed to have been “cured” of her homosexuality.

Richard Bruce Nugent (1906 - 1987)

While many writers and poets of the Harlem Renaissance may have been LGBTQ+, Richard Bruce Nugent was one of the only to be out during his lifetime.

He found community in Washington D.C., where he met Langston Hughes, which connected him to the literay circles of Harlem. His signature short story Smoke Lilies and Jade features a homosexual protagonist, making it a critical piece of early 1900s queer literature.

His queerness may have resulted in being less prominent in the Harlem Renaissance. However, Bruce continued live openly, publishing, acting, and serving as chair of the Harlem Cultural Council.

Angelina Weld Grimke (1880 - 1958)

Angelina Weld Grimke, named after her abolitionist-suffragist great-aunt, was born into a family committed to racial and gender equity. She committed her career to teaching and writing poetry, short stories, essays, and plays.

Her notable 1916 play Rachel, featuring an all-black cast, was a critical piece in combatting the film The Birth of a Nation, examining the impact of lynching. She stopped publishing in the 1920s, serving as an inspiration for the writers of the Harlem Renaissance, though not a participant.

Contemporary analysis of her erotic sonnets to women have led to recognition for Grimke as sapphic poet.

Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray (1910 - 1985)

Pauli Murray was a civil rights activist and lawyer. Their post-graduate work, States’ Laws of Race and Color, is an essential foundation of civil rights work.

They were also one of the founders of the National Organization for Women with Betty Friedan, coining the term “Jane Crow” to describe the intersectionality of being Black and female. They went on to be the first black person to receive a JSD from Yale and first woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest.

They were assigned female at birth, adopting the name “Pauli” to embrace an androgynous identity, though may have identified as a transgender man if they had that understanding during their lifetime.

Lucy Hicks Anderson (1886 - 1954)

Throughout her childhood, Lucy Hicks Anderson insisted on dressing and being treated like a girl. A doctor advising her mother to raise her as a girl.

As an adult, Lucy became a renowned chef among affluent families, eventually opening a brothel and speakeasy. Her generosity to the U.S. war effort earned her a place of respect in the community.

In 1945, her assigned sex was discovered. She and her husband were charged with perjury and fraud. During her trial, she proclaimed, “I defy any doctor in the world to prove that I am not a woman. I have lived, dressed, acted just what I am, a woman.”

Upon early release from a men’s prison, the couple reunited and lived quietly in Los Angeles.

William Dorsey Swann (1858 - 1954)

William Dorsey Swann is celebrated as first self-proclaimed “drag queen,” a term likely derived from “grand rag,” a nickname for masquerades. William held many private drags in Washington, D.C., where other Black men would gather and dance in women’s clothing, where a winner would be crowned “queen.”

After harsher penalties for cross-dressing were enacted in the 1880s, William was put in prison for 300 days. He was defeated and retired from drag, but the balls continued. William had been born into slavery around 1858. He originally came to Washington D.C. to find a well-paying job to support his family, but the move also connected him to the city’s queer community.

No known photographs of Swann survive. This 1903 postcard depicts two Black actors performing a cakewalk in Paris.

Sources:

“Angelina Weld Grimke.” Academy of American Poets

Duckett, Taylor Ajéwọlé . “Gladys Bentley: Pioneering Queer Performer.” Picturing Black History.

“Gladys Bentley.” National Museum of African American History & Culture.

“Hall of Honor Inductee: Bayard Rustin.” US Department of Labor.

“Lucy Hicks Anderson.” Queer Portraits in History.

“Pauli Murray.” National Museum of African American History & Culture.

“Pronouns, Gender, & Pauli Murray.” Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice.

Rothberg, Emma. “Marsha P. Johnson.” National Women’s History Museum, 2022.

Rothberg, Emma. “Pauli Murray.” National Women’s History Museum, 2022.

Samuels, W. (2012, October 10). “Richard Bruce Nugent (1906-1987).” BlackPast.org.

Sutherland, C. (2007, February 15). Angelina Weld Grimke (1880-1958). BlackPast.org.

Watson, E. (2007, January 19). Pauli Murray (1910-1985). BlackPast.org.